In strategy games, like puzzle games, you are offered an objective to complete, some kind of obstacle to pass, and you have to find out how to get past it. In Myst, this might be finding the right books that contain numbers that unlock a password somewhere else, but in a strategy game, it’s the question of: How do I siege my enemy’s fortress, or how to do I formulate a plan to outcompete my opponent who’s working towards the same goal as me?

When I play grand strategy games, my primary goal is to create a long-term plan for outperforming my opponents. This is a very open ended task, but it is in a way a puzzle. So this begs the question that I proposed at the start of the essay: Why do I enjoy Internet Riddle Games so much?

Well, I should firstly mention that I like a very specific selection of online riddle games. I, personally, do not enjoy the oldest and most famous online riddle game: Notpron. But I do respect it for pioneering the format, and beyond that, I think its foundational core is very solid. It’s the foundational core that the Hungarian game developer Aneninen adapted into his online masterpiece E.B.O.N.Y., which, if you know me, I adore from a design and gameplay point of view.

There’s a few reasons why E.B.O.N.Y. stands out to me as a beacon of content on the internet. First there’s the puzzles themselves, then inside of that there’s secondarily, the images, and then tertiarily there’s aesthetics. We’ll examine these one by one, and I’ll include no spoilers.

Let’s begin.

THE PUZZLES

E.B.O.N.Y. follows a very simple premise at its core that becomes wildly and exhilaratingly complicated and detailed as the game progresses. The puzzles present you with a few things: An image, some flavor text, and that’s about it. The image contains a scene (typically a very surreal and hard to understand scene, though there are much more normal ones than others) and generally a few clues, though they’re often hidden in some way.

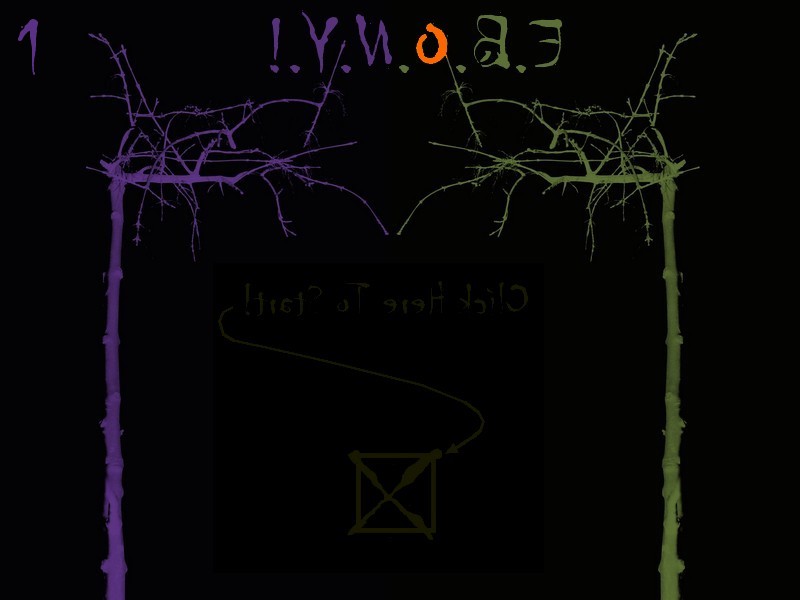

Sometimes there are things to interact with, like in the first level pictured below. There is a clickable element on the screen (that I’ll let you find for yourself if you’ve never played the game) and that’s paramount in beating the level. Other times there are clickable elements that lead to a subpage like a note or a sign. This clever use of images serves a triple purpose: They provide key information to the player to solve the puzzle, they contextualize the setting in a way that text cannot do on its own, and it also serves the aesthetic that I’ll talk about later.

Level one.

The images are, in a sense, the equivalent of what you’d see if you were playing a game like Myst, but instead of having an environment you control a player in, you are given a still snapshot of the world to view. This means that the image has to convey as much information as possible while still being stylistically in line with the aims of the artist. It’s a delicate balancing act of information and aesthetic because the image has to suspend the viewer’s disbelief that they are not actually sitting in front of a computer screen, but are actually, inside of this strange alternate world. However, at the same time, the image must guide the player as to their goals for the puzzle in tandem with the text and code.

Flavor text is simpler, but just as important in establishing both tone and information. Generally speaking, the flavor text contains less information than the image or code because it’s harder to be subtle with how text is used, though the text should never be ignored. Text, as a medium, is harder to hide puzzles in for a variety of reasons. The first reason that comes to my mind is that a puzzle based around, say, highlighted or bolded certain letters to reveal a message is very obvious and not difficult for a player to figure out.

This is because, unlike an image, text is designed to be functional. If bolding, or underlining, or italics were subtle, they wouldn’t be doing their job of conveying information or tone to a reader. The point of bolding is to make something stand out as important, italics is for quieter emphasis or in some cases, proper nouns, and underlining is to mark importance without large spacing unlike bolding, or in use as headers to create a more visible separation with the text underneath it.

Because of this, text has to be used more carefully in puzzles. Generally if flavor text is incorporated into a puzzle somehow, it’ll be used in a more subtle way, like a book cipher, where the cipher is not inside the text, but is rather outside of it, using the text as a bank of sorts to draw letters from to spell out a message.

This brings us to the third way that content is hidden: The code itself. For people who aren’t tech savvy, this is generally the point that they get very confused and maybe even give up. Code offers a golden opportunity to hide information inside of it for a variety of reasons. Code uses words like text (duh) but it doesn’t try to create a coherent line of text that you can plainly read.

For example: I can’t open Notepad++ and write “A black webpage with white text on it.” and get that. I have to actually input the HTML and CSS code that I want to actually achieve that.

That probably seems painfully obvious to everyone, but most people don’t realize the golden opportunity this provides for hiding puzzle information. It means that key information in solving a puzzle can be placed in plain sight, right amongst other words and numbers that are totally innocuous. You might see sometimes in the source code for pages that it talks about robots. What are these robots? Is this a clue? Clearly not, it appears on other webpages, but what does it mean!? It’s talking about search engines. “No robots” means the webpage won’t appear on regular search engines.

There’s a million nooks and crannies that hints can be placed inside and scouring through the code is something that players of E.B.O.N.Y. have gotten incredibly used to because it’s so easy to overlook simple things. Let’s talk a bit more about images though.

THE IMAGES

I touched on the necessity to balance the artistic intention of images with their functionality as puzzles. This is a very difficult balance to strike. Returning to what I was saying about the images acting as a snapshot: E.B.O.N.Y. has a very difficult stylistic question to ask itself: What is it actually supposed to look like?

This might seem like it has an obvious answer: E.B.O.N.Y. looks like E.B.O.N.Y., right? Well, it’s a bit more complicated than that. When we think about graphics in things like traditional video games, we can generally identify what the look its aiming for is. There are realistic looking games, pixel art games, cartoony games, which can be broken down further into things like cell shaded games, or anime games, or hand-drawn games. There are games that are text only, like text based adventure games. And we can identify this over time: We might point at a game like, say, Simcity 4 and say “Well it doesn’t look realistic at all to me.” but at the time it did. It was aiming for the standards of realism that were achievable in its day.

Cutting edge graphics, naturally.

This is why pinpointing what exactly E.B.O.N.Y. is meant to look like is difficult for me, and it’s a question I’ve dwelled on for a long time. First answer is: E.B.O.N.Y. looks realistic. After all, it uses still images, most of which are in some way obviously based on a photograph, even if it has been highly altered. Sure, that makes sense. E.B.O.N.Y. is a photorealistic game in the literal sense that its images are based on photographs. But I still don’t find that satisfactory because at the end of the day, E.B.O.N.Y. doesn’t look like real life.

It’s images are amazingly strange and surreal. When you look at them, you feel like you’re stumbling through an alternate dimension, which is basically what it’s aiming for. E.B.O.N.Y. wants to submerse you into its own world, and it begs for you to think that is real. In a sense, it is real. E.B.O.N.Y. is an idea, but it’s an idea that’s real inside the head of every player who plays the game, inside of every beta tester, and most importantly inside of Aneninen.

The images serve the purpose of taking the world of E.B.O.N.Y., all the text descriptions, all the dialogue with characters, and contextualizing it into a dream-like synthesis that it presents to you on each level. They are snapshots of the world that exists in your head as the player, as described in text by Aneninen, who has his version in his own head (Though if you were to ask Aneninen, he’d probably tell you that he is not the creator of E.B.O.N.Y. and more so a medium for it.)

If I am allowed to indulge my own pretentiousness in this essay, I might suggest the creation of a term like “paraimagery” to describe the nature of an image that is to serve a triple purpose of invoking an idea (like that of text), as a stand-alone piece of art, and also as an interactive puzzle for the viewer to analyze.

So, in a sense, we return back to the original answer that I had jokingly proposed. E.B.O.N.Y. does look like E.B.O.N.Y., primarily because it doesn’t look like anything else. In this sense, the classification of “What E.B.O.N.Y. looks like” cannot be answered because it defies the ability to be classified into a genre, instead settling outside the bounds of categorization on its own island of aesthetic, similarly to how it is in a metaphysical sense outside the bounds of our own reality, an idea that exists in our heads and not actually in our hands, across the door, or beyond the edge of a forest.

THE AESTHETICS

But aesthetics are not just images. The design choices of E.B.O.N.Y. run all the way from the visual, as in images, font, colors, ect, to the auditory, in the forms of the “tracs” that play in the background.

I am aware that the proper spelling is “Tracks” but the code refers to them as tracs.

It seems simple at first: Tracs are just the audio that plays in the background and nothing more, but that would be a massive understatement to the value that the tracs add to the experience of playing E.B.O.N.Y. mainly because a lot of solving the puzzles is sitting, thinking, googling, thinking some more, giving up to get coffee, coming back, remembering you forgot to water your plants, coming back again, and then doing more googling.

Tracs serve an important purpose being the background audio. They are seldomly valued, often muted, but discovering a new trac for the first time is an amazing experience (though most of them are now on Spotify so you can listen to them any time.) and that’s not even mentioning their amazing composition.

Aneninen created the tracs himself, which is definitely the best thing he could’ve done, not just because he is good at composing, but because that means the tracs are custom made to fit with E.B.O.N.Y. and nothing else. The tracs are designed to compliment the settings that they are used in. For example: Level one. Level one (also known as A1 in E.B.O.N.Y. circles) is dark, scary for some people, and is meant to act as the gateway between our world and E.B.O.N.Y.’s both literally and figuratively.

In the literal sense, A1 is the start of the game. It’s an introduction, with a very simple puzzle, and it’s just the first level of many, many levels inside this world. In the more metaphorical sense, what Aneninen wants to do as the developer, is immerse you into his world. He wants you to feel like you are literally leaving behind reality and stepping foot into the world of E.B.O.N.Y. for real.

This aesthetic choice is continued on the second level, A2. It’s more of the dark forest. It’s almost bichromatic, being composed of black and green, with only a hint of yellow on the level number and an important object that you are drawn towards because of its different color. The music, trac01, is droning, starting with a dark and low chord, before a high flourish of notes comes through. It’s uneasy, reflecting the unease you should be feeling towards the start. You’re in a forest at night, there’s nobody around, and you’re not quite sure that you’re doing. The text of the opening level reads: “...you’ve entered, which means there’s no turning back.”

This message is also two-fold. A duality that I’ve posited multiple times now is that of the literal and the metaphorical with E.B.O.N.Y. and it exists here too. In the literal sense, you’ve started the game. There’s no reason to return to the menu (although you obviously could if you wanted to), you have to progress to the next level. In the in-universe sense, your character is now inside of E.B.O.N.Y. and couldn’t turn back if they wanted to (even if you could literally return to the menu). And there’s the metaphorical: Now that you, the real you, has started the game, you can’t turn back because you can’t unsee the first level. Even if you stopped here, you’ve seen a bit of the game, and heard the first trac, and you can’t undo that.

The music of E.B.O.N.Y. is able to represent many things depending on where you are. It can feel dark and brooding when it needs to, but also light and airy when things aren’t so dark and grim. Characters in particular is where E.B.O.N.Y. is able to shine through its music. The characters are highly important to E.B.O.N.Y.’s story and as a break from solving puzzles. Being able to actually have dialogue with a character is unique amongst online puzzle games and was an element that I was particularly interested in using for my own.

The character’s theme songs vary wildly, with some sound straight out of horror films while others use unconventional music scales and sound heroic.

Text color is also used to denote differences in characters. One particular character who is menacing has a dark color, while other characters have brighter colors. One character who is in a terrible spot but is trying to make the best of it has a white color. Contrasted against the web page’s black background, it creates a sort of striking contrast between the darkness of her surroundings and the good that she has.

THE WRAP-UP

The short way of summarizing this entire essay is: You should play E.B.O.N.Y. Riddle Game. The longer way of summarizing this whole thing is: Be creative and intentional with how you choose to present your work. Every detail is important, even in ways that you may not realize. People are perceptive, and differences in tone, even if people don’t explicitly realize it, can be highly impactful.

Also, E.B.O.N.Y. is an amazing case study in puzzles, in video games, in the internet as a whole, and in how to defy a genre. It takes puzzles, a simple medium, and creates it into a beautifully intricate web. It also uses metaphysics to its advantage, creating a surreal and cerebral experience for the player, which is why the community that still exists for it is so dedicated to it, even though it is quite old now by internet standards.

Thank you for reading this essay, if it seems a bit rambly, that’s because I wrote it in one sitting. - Aurel